There's good news and bad news for the world's coral reefs. The good news is that the global coral bleaching that began in 2015 appears to be over, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Silver Spring, Maryland. The bad news, released on June 23, was that bleaching for three consecutive years had damaged three of all 29 coral reefs on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The forecast outlook is grim: Without significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, all of these reefs "will cease to function as functioning coral reef ecosystems by the end of the century," the UNESCO World Heritage Centre report predicts.

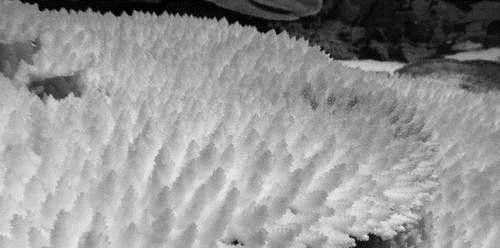

Bleaching occurs when excessively warm waters cause coralline algae known as symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae. Without these colorful algae, which use photosynthesis to provide nutrients to themselves and their hosts, corals would turn white or bleach. If the sea cools quickly, the algae will come back; if the bleaching continues, the coral will die. Coral reefs are ecosystems that support more than one million marine species. It is estimated that around 500 million people in the world depend on fishing and tourism for their livelihoods.

NOAA's Coral Reef Watch uses satellite-observed ocean surface temperatures and modeling to monitor and predict when water temperatures will rise high enough to cause bleaching. In the most recent case, seawater in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean basins began to rise in mid-2014 and began to bleach in 2015. The 3-year duration of this latest event is unprecedented; previous global bleachings have occurred within a year.

To understand what effects climate change may have on coral reefs, the World Heritage Center presented what they claim is the first study of its kind to coral experts at NOAA and elsewhere", scientifically quantifying the scale of the problem, making it possible to predict future location, and note the level that affects individual sites,” said Fanny Douvere, the center’s marine program coordinator. "This has never been done in the context of World Heritage," she added. The research team reviewed published reports on field observations and NOAA data. In addition to these 3 reefs, 29 suffered severe pollution and/or repeated exposure to seawater high enough to cause bleaching. Scientists have found that even remote, pristine reefs with minimal human damage, including Papahana Okaki in Hawaii and Aldabra Atoll in Seychelles, were severely bleached. "The third global bleaching event has seen the worst coral mortality ever recorded," the report states.

Coral reefs can recover from bleaching, but it takes 15 to 25 years. However, from 1985 to 2013, coral reefs in 13 of the 29 World Heritage-listed countries experienced bleaching more than twice per decade, that is, even before the most recent bleaching event, Australia The Great Barrier Reef has killed a large number of corals for the second year in a row. The team noted that if carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions continue to rise, the bleaching interval will get shorter and shorter. The report predicts that all 29 World Heritage reefs will be destroyed "under normal discharge scenarios" by the end of the century.

But even if carbon dioxide emissions are curbed, coral reefs face challenges from climate change. The Paris agreement set a goal of keeping the rise in average global temperatures below 2C above pre-industrial levels, but called for efforts to limit that increase to 1.5C. Any increase of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius has the potential to lead to "severe degradation of the vast majority of coral reefs," the report said. "However, limiting the rise in atmospheric temperatures will at least give coral reefs some time to adapt."

The report will be presented to the World Heritage Committee at a meeting in Kraw, Poland, on July 2. The World Heritage Centre and the International Union for Conservation of Nature have prepared a draft resolution for the committee. But the draft resolution on the coral reef report was "extremely disappointing", said Jon Day, a report author and resource manager for Australia's Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

While the draft resolution expresses its "greatest concerns" about the impact of climate change on World Heritage properties, any action has been delayed because when the committee met in 2018, it called for "further research into the current and potential impacts of climate change" . Day believes there is enough in the current report to develop a course of action. "It's really a failure rather than a solution to what is clearly a huge and growing problem," Day said.

Co-authors of other reports were more patient. "We are delighted" that the World Heritage Committee is considering a decision on climate change conservation policy, coral reef scientists Scott Heron and Scott Heron of the National Atmospheric and Atmospheric Administration wrote in a joint email. Although they agreed that a tougher stance now is welcome; "this year's actions pave the way for major changes in 2018," they wrote.